Algeria and Suspicions About Child Recruitment

In an international context that is witnessing a major decline in human rights issues, and the escalation of international tensions of a political, economic or cultural nature, and related to the national security of countries, and the consequent outbreak of armed conflicts in various parts of the world, this has had a profound impact on people’s living conditions and their way of life changed forever.

Given the great challenges faced by UN agencies in dealing with these emerging situations, with the aim of providing the minimum level of protection and secure access to rights, away from the sound of guns and the thunder of bullets.

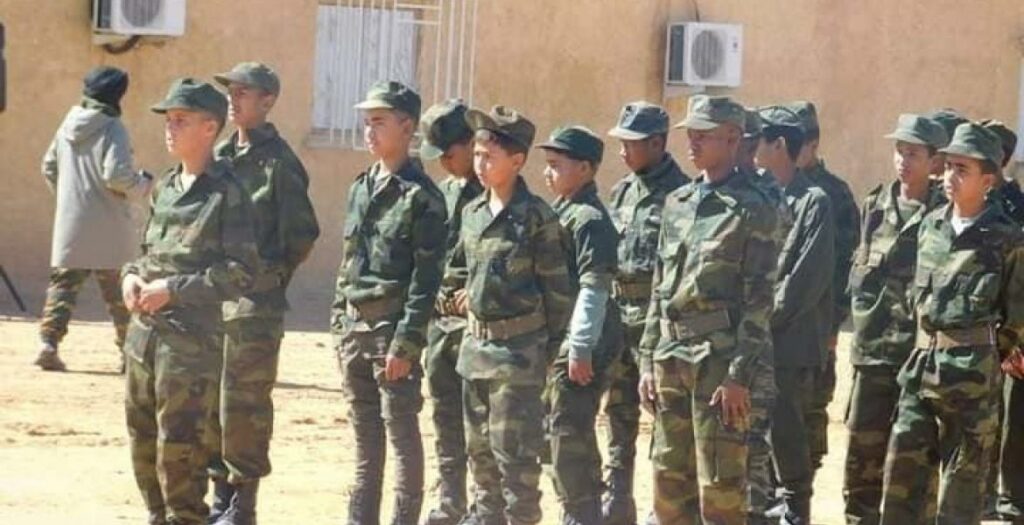

These efforts always clash with actors, especially non-state actors, who engage in internationally prohibited practices to strengthen their position in hostilities, such as the recruitment of children for armed conflict.

According to recent statistics from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), thousands of children are recruited and used in armed conflicts around the world, and acknowledged that between 2005 and 2020, more than 93,000 children were verified to have been recruited and used by parties to conflict.

In the face of this tragic situation, there is a total lack of vision for refugees and asylum seekers and any possibility of monitoring their conditions in the camps, and protection for vulnerable groups such as women and children is weak or non-existent, and the situation worsens if they are not offered international protection in accordance with the requirements of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, as in the case of the Sahrawi refugee camps in south-western Algeria.

From the above, these contexts call us to ask about the extent of the impact of the Sahara conflict on the conditions of Sahrawi refugee children in the Tindouf camps in Algeria, and is it possible to speak of recruitment processes for military service within the camps? And how can this serious violation be described from the perspective of international human rights law and international humanitarian law? And is there a way to bring the voice of victims and cases to international mechanisms?

Last but not least, he discussed the possibility for civil society organisations to contribute to reducing the frequency of systematic killings of children by recruiting them for military operations in the camps.

From another angle, to identify and determine the responsibility of the state hosting the Saharawi camps in the Tindouf region, in relation to the recruitment of Saharawi children into combatant services, either in relation to its contractual obligations under international human rights law or by virtue of its ratification of the Geneva Conventions and their protocols.

Researcher Abdelouahab Gain, president of Africa Watch, confirmed that although the Convention on the Rights of the Child includes all civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights of the child, it neglects the phenomenon of child recruitment, except for article 38 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which stipulates that all measures must be taken and which prohibits the participation of children under 15 years of age.

In this regard, the intervener explained that the Algerian authorities have never given a convincing answer on the protection of Saharawi children in the Tindouf camps, in the context of their interaction with the treaty bodies and the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, on the occasion of the examination of the scope of Algeria’s obligations under the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict.

The Committee noted that the Algerian National Authority for the Protection and Promotion of Children did not make any statement on the implementation of the Optional Protocol in relation to Sahrawi children who may have been recruited or used in hostilities.

The Committee on the Rights of the Child urged the Algerian authorities to amend their legislation so as to ensure the establishment of the minimum age for recruitment at 18 years, in its national territory, as well as in the armed organisation of the Polisario Front, whose activities it tolerates in its territory, and an emphasis on the establishment of an effective monitoring mechanism to ensure in practice that Saharawi children are not recruited.

Mr. Abdelouahab Gain added that Algeria’s delegation of its legal and judicial jurisdiction to a non-state military organisation complicates the possibility of improving the protection of children against widespread forced recruitment operations in the camps, in violation of Algeria’s obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child and its Optional Protocol on the involvement of children in armed conflict, as well as under the international Geneva Conventions and their annexed protocols.

Ms. Al-Mamia Hammi Al-Mamia Hammi, a civilian activist in Dakhla, reviewed the projects of sending Saharawi children in delegations of Saharawi students to study abroad, especially in Cuba in the 1980s and 1990s, and exposing them to systematic operations to alienate and forcibly place them in foreign societies of their culture that serve as nurseries to prepare child soldiers and child labourers, who are only fit for harsh military service, hard and forced labour as well as participation in military operations and prolonged ideological indoctrination processes.

Interacting with a question from the conference facilitator on the effects on Saharawi children as a result of their recruitment and exploitation in work related to hostilities, the intervener stated that these child soldiers are exposed to strong shocks, which hinder their academic studies and psychological development, limit their growth within the social fabric naturally, and furthermore increase their aggressiveness and tendencies to violence due to their exposure to psychological pressures at an early age.

El Mamia Hammi added that the recruitment of Saharawi children is entirely the responsibility of the Algerian government, due to its failure to fulfil its responsibility to protect Saharawis in the camps, especially children, as well as its continued supply of arms to the Polisario, which end up in the hands of young children due to the Polisario’s insistence on providing its ranks with an additional number of soldiers, due to the cases of desertion and abandonment that affected the Polisario military groups two decades ago due to the lack of horizons in the camps and desire to seek a better future in the diaspora.

The spokesperson launched an appeal to all civil society associations to push for a halt to the recruitment of adolescents and minors in the camps and the need to draw lines and programmes to help former recruits return to school and to their natural environment to complete their development, instead of embracing the barrels of guns.

The recruitment of children has become a worrying phenomenon on a global and continental level, since, according to official statistics, there are 120,000 child soldiers in Africa, an alarming figure when compared to the number of armed conflicts that arise on the African continent.

In this sense, the Spanish activist, Pedro Altamirano, explained the origins and motives that fuel armed conflicts and wars in Africa, which lead to the use of children as soldiers in hostilities between combatants, or in activities related to these military operations and battles.

He also stressed that this is a constantly recurring pattern resulting from the failure of states to enforce the rule of law and justice, expand rights and freedoms, transparency in governance and ensure equality, as well as the widespread feeling of insecurity and poverty and the absence of a vision for the future to improve the situation of the people.

Pedro Altamirano, said that ending terrorism and preventing child recruitment requires approaches to end the poverty resulting from disastrous colonialism and the worst effects on people’s capacities and destinies, as well as direct action by civil society organisations based on the increasingly important principles and standards of civil diplomacy.

In this context, he adds that all these approaches to put an end to the recruitment of children in the Tindouf camps will not be completed once and for all unless the political parties, the Spanish pressure groups, coming from the European Union, exhaust the sources of financing of the Polisario organisation, which emanate from the separatist movement ETA, and by Somar, which managed to make one of the members of the Polisario organisation its representative in the Spanish Parliament.

At the conclusion of the conference, Abdelouahab Gain added that this debate aims to provide human rights defenders, activists and all interested parties with an overview of the legal framework applied in relation to international humanitarian law on the issue of recruitment and use of children in armed conflict, while providing an insight into the Saharawi context and contributing to improving knowledge of the international legal framework, in order to reduce the recruitment and use of child soldiers in hostilities in the Tindouf camps.

Source : Atalayar